Discover our exclusive interview with Michel Mousseau, self-taught painter. To coincide with our exhibition “Michel Mousseau, The 60s“, the artist shares with us his unique career path, his artistic influences and his singular vision of painting. From his first aesthetic revelations to the nudes and still lifes that are emblematic of his work in the 60s, discover the thoughts and emotions that have shaped his work. Dive with us into Michel Mousseau‘s captivating universe and explore the themes and techniques that make his work a vibrant celebration of light and colour.

Q1 Can you tell us about your artistic career and what led you to become a painter?

I’m self-taught, with no formal artistic training. When I was a teenager at lycée, I was lucky enough to see some authentic paintings by Soutine and Modigliani at the home of a friend’s mother, who was a painter herself. It was a revelation.

Also at school, the short films on painting from all periods shown to us in art class by our teacher, Mr Jean Couy, a painter, were very formative for me. He introduced me to Cézanne.

I started drawing very early on, making lots of small, very precise drawings, which I unfortunately threw away. After that, I went to evening painting and drawing classes on Boulevard du Montparnasse in Paris. I was very assiduous but never received any advice from the painters or draughtsmen who taught there.

My first aesthetic emotion was discovering the ocean at Pornic. Coming from Paris by bike, I remember the violence of that dazzle, that horizon so far away from the sea.

I must add that what seems to me to have been very formative in my journey as a painter are the worlds of my two grandparents. One was a blacksmith, the other a baker. I have an image of the forge, it was a very dark place. And there was this glint of red iron on the anvil in the middle. These two worlds, one of Black and fire, the other powdery, flour-white, making everything light and silky, including the floor and walls, these two worlds created a chromatic base that I have never stopped developing.

Q2 Which artists or artistic movements have most influenced your work, particularly in the 60s?

I discovered Cézanne, Rembrandt and Gainsborough. Cézanne and Matisse are familiar to me. I discovered Les Ménines by Vélasquez at the Prado in Madrid. It was also a time when I saw major exhibitions devoted to Picasso and Poussin, whose The Seasons touched me deeply. But what really struck me first in painting was De Staël. Klee, Mondrian and Joan Mitchell are among the painters whose work particularly interests me. Jean Hélion was also one of my discoveries at the time.

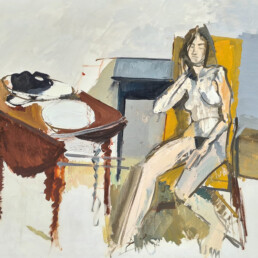

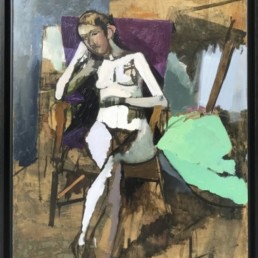

Q3 What inspired you to create the nudes and still lifes presented in this exhibition?

I was struck by the work of Richard Lindner, for example. He’s an American painter. The fundamental problem with his work is the relationship between things and the flesh, the flesh being a particular element of what surrounds us. I loved painting nudes, with their design and movement.

I see my work as a painter as a quest, a search, to which I associate the notion of pleasure. For me, research and pleasure are two words that define my attitude to painting. I left the Sorbonne and the wonderful Jankélévitch to live painting.

Q4 Can you explain your choice of colours and textures in your 60s paintings?

I come back to the image of the forge. This question of origin, in many ways including the reference to Courbet, is at the heart of my research. Courbet and the Origin of the World rather than the Impressionists. Perhaps that’s where my taste for black comes from, because black generates light, receives light, whereas yellow reflects it. Yellow is brilliant, it’s like gold. Soulages only worked with black, but his blacks are often coloured.

Over a long period of time, I’ve been interested in the “Fabrique du Noir”, or the Black as internal light. In other words, black is either red or blue, hot or cold, it is itself a varied colour, whereas lemon yellow is always lemon yellow, it’s a bit silly, it only reflects lemon yellow.

I insist on the continuous nature of my work. If there are periods, they are periods of continuity, the continuity being light and therefore light from what I call “The true colour of things“. It’s a title given to me by the poet Georges Schehadé. The true colour of things, that’s what I’m looking for.

But let’s not forget the fundamental pleasure of spreading colour, of receiving colour in the eye – it’s mysterious, it’s magnificent.

Q5 How do you approach the theme of intimacy in your nudes?

My subject is painting. For me, it’s not about reproducing or representing “things”, an object, a body or a landscape, but about capturing what catches the light.

My Nudes have been described as “pensive”. Thoughtful, yes, in the sense that I don’t tell stories. I’d say more detached, with a certain contemplative distance. It’s completely sensual, in the sense that a human body is not an object but a receptor of light.

Painting is first and foremost about seeing and making others see. Revealing without getting bogged down in anecdote. Painting expresses reality in all its transience and strangeness. It gives to see, it is to be seen. My painting is neither descriptive, narrative nor explanatory. I don’t paint objects or nudes, but I paint the light on objects and bodies in relation to the space in which they are.

So there is no question of intimacy, even when the subject is a human body. The human body, along with its surroundings, is a place that is taken over by painting, which searches for and through itself.

I see continuity in my work, I repeat. Continuity in the search for light, for matter, for that which resists the superficial gaze.

To paint nudes is not to try to capture or provoke desire or eroticism; it’s to investigate the enigma of reality that the painter’s gesture attempts to define through form, texture and colour. It is up to the viewer, if they so wish, to interpret the motif, the subject if that is what interests them.

Q6 How did the 60s influence your art?

During the period when I painted the canvases you are exhibiting, I wasn’t at all on the lookout for political or other events. At that time I lived in an artistic and intellectual milieu that included Roland Topor, Olivier O. Olivier and the regulars at Castel. In the theatre, I worked with Georges Wilson, Georges Vitaly and Daniel M. Maréchal, saw Pierre Arditti, Claude Brasseur and Sylvia Montfort, and was in contact with gallery owners Margueritte Motte and Robert de Bolli. I met a lot of poets, including André Salmon and Georges Schehadé. I live between Paris, Brittany and the Var.

My annual visits to the Cotentin region began in 1964. There I rediscovered the immensity of the skies and the sea. This was to give a new direction to my work.

Q7 What message or emotion would you like to convey through your work?

Open your eyes. To look. Seeing, that’s my project. I’m an optical glutton. The viewer is free.

How can we not hope that art remains at the heart of our lives?

Q8 What do you think is the place of art in today’s society?

Today’s art is more oriented towards representation and illustration than towards exploration. Contemporary art is more about DIY. I would say that Picasso was a genius at tinkering.

I ask the question, what does it mean to ‘see’? Because if you can’t see any more, what’s left? There’s nothing left. What is dying, if not no longer seeing? In short, painting is like a touchstone for existence.

Painting is a gesture of recognition, a form of homage to Creation. It is also a privileged meeting place with oneself and with those who have contributed to making the world a living place.

Céline Fernandez

Forte d’une expérience de 15 ans dans le marketing et la communication, Céline a travaillé pour de grandes sociétés telles que le Public Système, le Groupe Galerie Lafayette et plusieurs agences de communications. Depuis plus de 4 ans, elle gère la communication de la galerie à travers le site internet, les réseaux sociaux et les médias traditionnels.